In dreams begin responsibilities. But it’s no less true that in dreams begin irresponsibilities. The menu, in terms of our possibilities in both those respects, is well-nigh infinite. Science fiction is that menu.

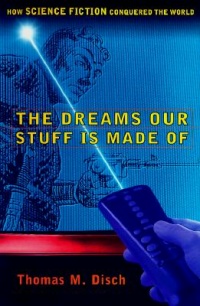

Title: The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World

Author: Thomas M. Disch

Year: 1998

Rating: 2/5 stars

I’m always interested in reading opinions about science fiction from those who actually write it. And so I was sure I’d enjoy this book, and I did, even though I can’t agree with everything Disch has to say. Rather than being a straightforward work of criticism or history of the genre, the intended focus here is, as Disch tells us, the impact of science fiction on our world:

I’m always interested in reading opinions about science fiction from those who actually write it. And so I was sure I’d enjoy this book, and I did, even though I can’t agree with everything Disch has to say. Rather than being a straightforward work of criticism or history of the genre, the intended focus here is, as Disch tells us, the impact of science fiction on our world:

In short, science fiction has come to permeate our culture in ways both trivial and/or profound, obvious and/or insidious. And its effects have not been limited to the sphere of “culture,” in the narrow sense of one art form’s influencing others. The influence of science fiction, as we shall witness abundantly in the pages ahead, can be felt in such diverse realms as industrial design and marketing, military strategy, sexual mores, foreign policy, and practical epistemology — in other words, our basic sense of what is real and what isn’t.

Despite such a clearly stated purpose, the book fails to make any overall, unified point, and ends up being merely the rambling thoughts and recollections of one particular SF writer. Each chapter sets out to discuss one particular aspect of science fiction’s cultural impact, but there is a lot of sidetracking into topics not really related (or only loosely so) to the chapter at hand. That’s not to say it isn’t worth reading, for there is certainly plenty of fascinating material here. I’m just saying it’s not the most well-oraganized book I’ve ever read.

Disch spends a couple of chapters discussing some of the important “fathers” of the genre: Verne, Wells, Stapledon, Clarke. And, strangely, Edgar Allen Poe; I find Disch’s argument for considering Poe part of that group to be pretty weak and unconvincing. There is a chapter on how SF influenced people’s views about nuclear danger and the Cold War. There’s another chapter on Star Trek (which Disch didn’t think very highly of). A chapter on feminism. One on SF and religion. One on politics and the military (which frequently makes reference to Heinlein and Pournelle). A chapter on aliens, and how they are often stand-ins for the Other in real life: women, different ethnic groups, etc. The final chapter considers science fiction’s future, ending with the quote at the top of this review.

My major problem with the book is Disch’s largely negative portrayal of the genre and its fans. He recognizes, once or twice, that there are two sides to SF: the pulpy, mass-market entertainment side that caters to the lowest common denominator, and the more intellectual side of at least a portion of SF literature. However, he spends a disproportionate amount of space on the former, and not much on the latter. More than once he implies that SF fans are, in general, gullible simpletons who believe in UFO’s, Scientology, and other silly things, calling them “the SF faithful” or “true believers.” Surely there is that segment of fandom out there; but to use it as a general stereotype of SF fans, as Disch seems to do here repeatedly, is simply ridiculous.

The book strayed off-topic quite a bit, and Disch comes across as bitter, or annoyed, or amused, or dismissive, at various times — and, to be fair, intelligent and thoughtful at other times. I think what I found most interesting were the little tidbits of his experiences scattered through the book. Such as the flaky characters he met at a writer’s workshop. Or the very unusual invitation Disch once received from Theodore Sturgeon and his wife. I don’t think this book succeeds at its intended purpose, or represents a well-rounded look at the genre; but it is, nevertheless, an interesting read from one of SF’s recently departed voices.

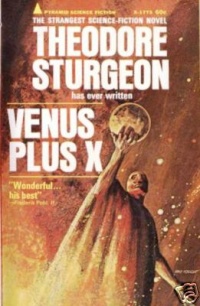

On the front of my vintage paperback copy of Venus Plus X is the declaration: “the strangest science-fiction novel Theodore Sturgeon has ever written.” I can’t speak to the “-est” part (haven’t read enough of his work), but the rest of that statement is accurate enough; this is definitely a strange book. It’s a utopian story that focuses primarily on gender issues, viewing sexual differences and competition as the pivot on which society turns. Like many utopian novels, this one makes some good points here and there, but ultimately ends up being (a) unconvincing, and (b) a little bit creepy.

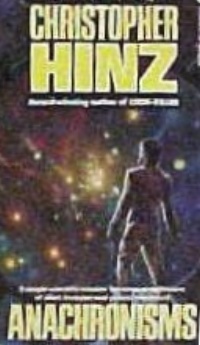

On the front of my vintage paperback copy of Venus Plus X is the declaration: “the strangest science-fiction novel Theodore Sturgeon has ever written.” I can’t speak to the “-est” part (haven’t read enough of his work), but the rest of that statement is accurate enough; this is definitely a strange book. It’s a utopian story that focuses primarily on gender issues, viewing sexual differences and competition as the pivot on which society turns. Like many utopian novels, this one makes some good points here and there, but ultimately ends up being (a) unconvincing, and (b) a little bit creepy. I find Christopher Hinz mildly frustrating in that he possesses plenty of writing talent but only a very small body of work in which to show it. He turned out four novels of moderate to high quality between 1987 and 1991, and that’s all (besides some comic book writing he’s done), and that’s a shame because I think he could have offered so much more. His Paratwa trilogy is one of my favorite works of science fiction ever, particularly the initial installment, Liege-Killer (which some of you know as my identity on several forums). Actually, I don’t know why I let so many years pass before reading his standalone novel, Anachronisms, but I’ve taken care of that little oversight at last. As it turns out, this novel unfortunately isn’t in the same class as the Paratwa series. There’s nothing especially unique or groundbreaking about it — in fact it’s constructed from some fairly familiar and well-worn sci-fi tropes. For what it is, though, it’s skillfully written, with engaging plot and credible characters, and keeps the reader’s interest on target from start to finish.

I find Christopher Hinz mildly frustrating in that he possesses plenty of writing talent but only a very small body of work in which to show it. He turned out four novels of moderate to high quality between 1987 and 1991, and that’s all (besides some comic book writing he’s done), and that’s a shame because I think he could have offered so much more. His Paratwa trilogy is one of my favorite works of science fiction ever, particularly the initial installment, Liege-Killer (which some of you know as my identity on several forums). Actually, I don’t know why I let so many years pass before reading his standalone novel, Anachronisms, but I’ve taken care of that little oversight at last. As it turns out, this novel unfortunately isn’t in the same class as the Paratwa series. There’s nothing especially unique or groundbreaking about it — in fact it’s constructed from some fairly familiar and well-worn sci-fi tropes. For what it is, though, it’s skillfully written, with engaging plot and credible characters, and keeps the reader’s interest on target from start to finish. If you were to pick up a book by a known science fiction writer (Kim Stanley Robinson), from a known science fiction publisher (Tor), and with a title like Remaking History, would it not be reasonable to have some expectation of what you’d find in it? As for me, I somehow expected this to be a collection of alternate history stories, with maybe some time travel in the mix as well; that doesn’t seem like such a leap, does it? If you would make that leap, however, like I did, you’d be wrong. Not a single story in this volume fits that description in any strict sense. Of course, the author can’t really be blamed for my faulty assumption, so it’s not for that reason that I consider this collection a letdown. No, my disappointment has more to do with the fact that few of these stories entertained me much, or had much of importance to say; or that, when they did have something to say, the commentary was housed within narratives so dull I couldn’t be bothered to care. I was also, I admit, a little put off to find that about a third of the stories are not even science fiction, but what can only be considered “mainstream.”

If you were to pick up a book by a known science fiction writer (Kim Stanley Robinson), from a known science fiction publisher (Tor), and with a title like Remaking History, would it not be reasonable to have some expectation of what you’d find in it? As for me, I somehow expected this to be a collection of alternate history stories, with maybe some time travel in the mix as well; that doesn’t seem like such a leap, does it? If you would make that leap, however, like I did, you’d be wrong. Not a single story in this volume fits that description in any strict sense. Of course, the author can’t really be blamed for my faulty assumption, so it’s not for that reason that I consider this collection a letdown. No, my disappointment has more to do with the fact that few of these stories entertained me much, or had much of importance to say; or that, when they did have something to say, the commentary was housed within narratives so dull I couldn’t be bothered to care. I was also, I admit, a little put off to find that about a third of the stories are not even science fiction, but what can only be considered “mainstream.” I’m happy to say I’m all caught up on essential Bester. Last year I had the pleasure of reading

I’m happy to say I’m all caught up on essential Bester. Last year I had the pleasure of reading