I just finished a fascinating book called Dream Makers: Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers At Work, by Charles Platt. It’s a book of author profiles based on interviews Platt (an editor and writer himself) conducted in the late 1970’s. The work was originally published in two paperbacks in the early 80’s; this 1987 hardcover volume is a “new and revised” merger of those two earlier editions. The authors covered are: Isaac Asimov, Jerry Pournelle, James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon), L. Ron Hubbard, Algis Budrys, Harry Harrison, Brian Aldiss, J. G. Ballard, Michael Moorcock, Frederick Pohl, Theodore Sturgeon, Harlan Ellison, A. E. van Vogt, Philip K. Dick, Ray Bradbury, Philip Jose Farmer, Thomas Disch, Arthur C. Clarke, Frank Herbert, Fritz Leiber, Piers Anthony, Keith Laumer, Alfred Bester, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and Stephen King.

I just finished a fascinating book called Dream Makers: Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers At Work, by Charles Platt. It’s a book of author profiles based on interviews Platt (an editor and writer himself) conducted in the late 1970’s. The work was originally published in two paperbacks in the early 80’s; this 1987 hardcover volume is a “new and revised” merger of those two earlier editions. The authors covered are: Isaac Asimov, Jerry Pournelle, James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon), L. Ron Hubbard, Algis Budrys, Harry Harrison, Brian Aldiss, J. G. Ballard, Michael Moorcock, Frederick Pohl, Theodore Sturgeon, Harlan Ellison, A. E. van Vogt, Philip K. Dick, Ray Bradbury, Philip Jose Farmer, Thomas Disch, Arthur C. Clarke, Frank Herbert, Fritz Leiber, Piers Anthony, Keith Laumer, Alfred Bester, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and Stephen King.

Platt’s introduction tells us something about his goals:

I started doing profiles of science-fiction authors (and other writers of imaginative literature) because I knew from personal experience that they could be just as interesting — sometimes, just as bizarre — as their own books. Also, I believed that the personality of the writer was relevant to his work. Most critics focus exclusively on the text itself, as if it might be “improper” to make deductions or inquiries about a writer’s life. To me, this is snobbish and arbitrary. We can appreciate their work more if we know more about them as people.

And I do know more about these authors as people, after reading these profiles. I learned a lot about these authors, about the way they live, the way they write, the things they’re passionate about, that made me appreciate many of them more (and a few of them less). Most of the material presented is direct quotation from the authors, with a minimum of Platt’s commentary. Which is fine, because Platt’s comments and questions are rather dull most of the time (with a few insightful opinions now and then). It’s the words of the writers themselves that really make this book shine. I’d like to share some of the more interesting quotes and tidbits of information I picked up from this book.

Alice Sheldon (James Tiptree, Jr.) and her husband both worked for the CIA in its early days, in relatively important positions (cool — a spy and a science fiction writer). Alice had a degree in psychology, and one of her comments was:

“Man does not change his behavior, he adapts to the results of it. That is, to me, the most grisly truth I learned from psychology.”

Harry Harrison shared his opinions about the corruption of sf awards, the lack of respect (and decent pay) for sf writers, and the dirty behavior of publishers and Hollywood. It all culminates in this recollection:

“Someone once sent me a clipping from some magazine, an interview with George Lucas, saying ‘I grew up reading science fiction, I really was a fan of science fiction, but I didn’t like things written by people like Heinlein or Bradbury, I thought Harry Harrison was my god, and I enjoyed everything he wrote.’ That kind of thing. I thought, ‘Well! Why the hell didn’t you write to me and have me do a god damned script for you, you know, if that’s what you feel, old son, I’d be very happy to come over and make some money from this rotten field.’ Oh there’s no justice in this field.”

Frederick Pohl is (or was back then) quite politically active; he also sometimes lectured/preached at churches (mostly Unitarian). But he was pessimistic about whether anyone really listened to him:

“I remember talking to a group in Chicago once and saying that the primary requisite for achieving a viable relationship between our society and the planet’s ecology was individual self-control. They stood up and cheered me. Then the next speaker said exactly the opposite and they stood up and cheered him too.”

A. E. van Vogt spent much of his interview babbling about Dianetics, est training, and other psycho-nonsense. He came across as a total crackpot, saying that psychology needed saving and he might be the one to save it. Mighty humble, that one.

Philip K. Dick talked about…. well, the kooky stuff PKD is so well known for. From much of what he said, his unfortunate mental problems are all too apparent. However, even with his problems, he came across as more modest, intelligent, and likable than van Vogt.

Frank Herbert was also an amateur scientist and inventor. He and an electronics engineer friend once tried to design their own new kind of computer. He also experimented with harnessing wind power and came up with some pretty cutting-edge designs.

Piers Anthony is a hyperactive tour-de-force. He talks fast, moves fast, works fast — fast and non-stop. And even though he has a very successful writing career, he lives humbly:

“I am not foolish about money at all. I don’t waste it, you don’t see me going off and buying Cadillacs, no you see me out there splitting wood, because we have a wood-burning stove, and solar-powered water heating, if the sun doesn’t shine we don’t bother with hot water, because I don’t like paying fuel bills. I’m a miser!”

Alfred Bester had one of the most fun profiles to read. Asked about his method of dealing with rejection letters, his answer was: “drink more!” Did you know Bester, while an editor for Holiday magazine, was responsible for talking Peter Benchley into turning what was then just a story into an entire novel — Jaws? When asked about retirement, he said:

“Retire? Yeah, I want to retire with my head in the typewriter. That’s my idea of retirement.”

One of the things I liked about Platt’s style was that he helped to give a feel for the authors by describing their homes (most of the interviews were in person), and particularly their work areas used for writing. There was quite a variety, from Ballard’s desk by a big window facing his back yard, to Anthony’s office barn, to Farmer’s windowless basement room with walls covered in erotic art.

There’s a lot more I could mention — this book is full of great stuff! And somehow, in some mysterious way, my “to read” list has grown longer. Funny how that happens all the time. 😆

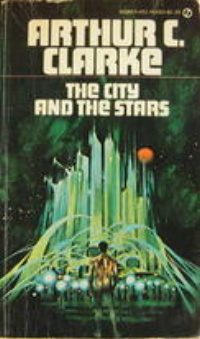

A city that has stood for a billion years, protecting its population on a future Earth long since abandoned and turned barren. Matter-manipulating technology capable of sustaining that city in perfect condition, and providing anything the inhabitants need or desire. Memory banks that hold each person’s pattern, allowing them to reincarnate over and over again, providing them with a new body each time. A humanity that has long ago lost much of its heritage and knowledge of its past, and now lives a safe but limited existence, frightened of the outside world and their innate human curiosity. And one unique individual who embraces his curiosity, setting forth on a quest for answers that will change his world. Such are the concepts that make up The City and the Stars, one of Arthur C. Clarke’s earliest novels (actually a rewrite of his first novel, Against the Fall of Night, with which he was dissatisfied).

A city that has stood for a billion years, protecting its population on a future Earth long since abandoned and turned barren. Matter-manipulating technology capable of sustaining that city in perfect condition, and providing anything the inhabitants need or desire. Memory banks that hold each person’s pattern, allowing them to reincarnate over and over again, providing them with a new body each time. A humanity that has long ago lost much of its heritage and knowledge of its past, and now lives a safe but limited existence, frightened of the outside world and their innate human curiosity. And one unique individual who embraces his curiosity, setting forth on a quest for answers that will change his world. Such are the concepts that make up The City and the Stars, one of Arthur C. Clarke’s earliest novels (actually a rewrite of his first novel, Against the Fall of Night, with which he was dissatisfied).

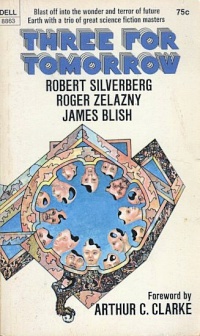

This nifty little volume contains three novellas by three well-known SF writers — but not just any random novellas. These three pieces are the result of an interesting literary project, and they were written especially for this purpose. To be more specific: the authors were presented with a short essay written by Arthur C. Clarke setting forth a general theme for a story, and then those authors took that theme and did what they do best: they wrote a story based on Clarke’s essay, attempting to work within that framework while interpreting it in their own different ways, filtering it through their own unique imaginations. As it turns out, none of these three novellas are remotely similar to each other; and only one (Silverberg’s) seems to me to be a good fit for the concepts laid out by Clarke. That in itself doesn’t mean the other stories are bad. It simply means that this little literary experiment wasn’t quite as successful as it could have been. I liked two out of the three novellas, so hey, I can’t complain too much.

This nifty little volume contains three novellas by three well-known SF writers — but not just any random novellas. These three pieces are the result of an interesting literary project, and they were written especially for this purpose. To be more specific: the authors were presented with a short essay written by Arthur C. Clarke setting forth a general theme for a story, and then those authors took that theme and did what they do best: they wrote a story based on Clarke’s essay, attempting to work within that framework while interpreting it in their own different ways, filtering it through their own unique imaginations. As it turns out, none of these three novellas are remotely similar to each other; and only one (Silverberg’s) seems to me to be a good fit for the concepts laid out by Clarke. That in itself doesn’t mean the other stories are bad. It simply means that this little literary experiment wasn’t quite as successful as it could have been. I liked two out of the three novellas, so hey, I can’t complain too much.