The sf writer cannot avoid man’s problems; by the very nature of his craft, he must meet them head on. That is sf’s challenge, and it is as big as the future of mankind.

Title: The Craft of Science Fiction: A Symposium on Writing Science Fiction and Science Fantasy

Editor: Reginald Bretnor

Year: 1976

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars

Here’s one of those “advice on how to write from the writers themselves” books, which I picked up not because I have any goals of writing myself but simply because I like reading what sf writers have to say about their field. This is one of several such volumes helmed by the same editor back in the 1970’s, and is a fairly interesting collection of essays for any sf fan who also likes reading works about sf. Strange fellow though, this Bretnor. His introduction provides some insightful thoughts on sf, but things get a little weird when he starts professing his belief that clairvoyance, dowsing, and other assorted woo is “proven.” Uhhh, yeah, whatever. Anyway, who cares what the editor has to say? What’s important is what the writers themselves have to share. Here’s a rundown of their contributions and a few comments on each:

Here’s one of those “advice on how to write from the writers themselves” books, which I picked up not because I have any goals of writing myself but simply because I like reading what sf writers have to say about their field. This is one of several such volumes helmed by the same editor back in the 1970’s, and is a fairly interesting collection of essays for any sf fan who also likes reading works about sf. Strange fellow though, this Bretnor. His introduction provides some insightful thoughts on sf, but things get a little weird when he starts professing his belief that clairvoyance, dowsing, and other assorted woo is “proven.” Uhhh, yeah, whatever. Anyway, who cares what the editor has to say? What’s important is what the writers themselves have to share. Here’s a rundown of their contributions and a few comments on each:

Poul Anderson, “Star-flights and Fantasies: Sagas Still to Come.” This one’s rather dry, with not much of importance to say.

Hal Clement, “Hard Sciences and Tough Technologies.” A decent article on the use of science in sf and the importance of internal consistency.

Norman Spinrad, “Rubber Sciences.” One of the best essays in the book; it covers some of the same ground as Clement, but from a different perspective. Spinrad says what’s important in sf is plausibility, and not necessarily a rigid deference to scientific fact. He sums up by saying science fiction writers are….

… the poets of the future, the seers of human destiny. Hard science, soft science, or rubber are tools of the trade, means to the end of visionary insight and artistic creation. They should never be mistaken for the end itself.

Alan E. Nourse, “Extrapolations and Quantum Jumps.” Focuses largely on that all-important fictional element, the premise, as well as other fiction basics. Solid article.

Theodore Sturgeon, “Future Writers in a Future World.” This was a pure joy to read. Sturgeon does a better job than anyone else in this volume of getting across the sheer sense of wonder of science fiction, and his essay is full of enthusiastic inspiration for future writers and valuable advice on where to find story ideas. He also stresses the importance of connecting your ideas to real human concerns:

And whatever your idea or statement, gimmick, gadget or message, you will (to be read) encase it in love, and pain, and greed, and laughter, and hope, and above all loneliness.

Jerry Pournelle, “The Construction of Believable Societies.” A good look at the need for social depth — what we often call “world building” — in sf.

Frank Herbert, “Men on Other Planets.” Herbert makes some great points about sf’s ability to escape our society’s unexamined assumptions and play around with them. He also quite correctly warns the potential writer that there’s more to writing sf than thinking up an idea — the development of that idea is the crucial thing.

Katherine MacLean, “Alien Minds and Nonhuman Intelligences.” MacLean chose an intriguing topic, but her thoughts on the matter were scattered and unfocused and, to be honest, boring.

James Gunn, “Heroes, Heroines, Villains: the Characters in Science Fiction.” Pretty self-explanatory. Solid article on the importance of characterization.

Larry Niven, “The Words in Science Fiction.” On how to add some linguistic depth to your fiction. Interesting.

Jack Williamson, “Short Stories and Novelettes.” A few words on the particular strengths and weaknesses of the shorter fictional forms.

John Brunner, “The Science Fiction Novel.” And here’s Brunner on the other end of the spectrum.

Harlan Ellison, “With the Eyes of a Demon: Seeing the Fantastic as a Video Image.” A long and involved article on writing screenplays for television and film. I didn’t find it that interesting myself, but I’m sure it would be helpful to anyone looking to do that kind of work.

Frederik Pohl, “The Science Fiction Professional.” A rather tedious essay on the business aspects of being a writer — all about agents, publicity, contracts, and such.

Basically it’s a few boring articles, mixed with a few really pleasurable ones, with a lot more falling somewhere in between. I’d recommend this book to would-be writers; for anyone else, it just depends on how much interest you have in this sort of thing.

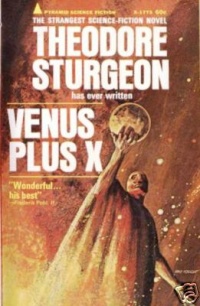

On the front of my vintage paperback copy of Venus Plus X is the declaration: “the strangest science-fiction novel Theodore Sturgeon has ever written.” I can’t speak to the “-est” part (haven’t read enough of his work), but the rest of that statement is accurate enough; this is definitely a strange book. It’s a utopian story that focuses primarily on gender issues, viewing sexual differences and competition as the pivot on which society turns. Like many utopian novels, this one makes some good points here and there, but ultimately ends up being (a) unconvincing, and (b) a little bit creepy.

On the front of my vintage paperback copy of Venus Plus X is the declaration: “the strangest science-fiction novel Theodore Sturgeon has ever written.” I can’t speak to the “-est” part (haven’t read enough of his work), but the rest of that statement is accurate enough; this is definitely a strange book. It’s a utopian story that focuses primarily on gender issues, viewing sexual differences and competition as the pivot on which society turns. Like many utopian novels, this one makes some good points here and there, but ultimately ends up being (a) unconvincing, and (b) a little bit creepy.