He sat for a moment, stunned at what he’d done, stunned at what had happened, wondering what he would do the rest of his life with the memory of it. Then he zipped up his pants.

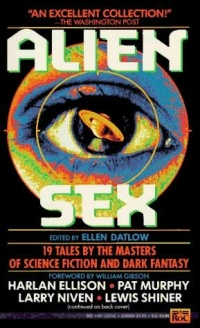

Title: Alien Sex

Editor: Ellen Datlow

Year: 1990

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars

Science fiction, obviously, has an interest in aliens. And let’s face it, everyone has an interest in sex. So it’s not surprising to occasionally find both interests coinciding in the same place. In this volume you’ll find nineteen tales of sex seen through the lens of science fiction (with a bit of fantasy and horror mixed in as well). These stories run the gamut, from thought-provoking to dull to incomprehensible; there is enough of substance here, however, to make this a worthy contender for the reader’s attention. The stories also vary in their approach to the anthology’s theme; while some are straightforward speculations on human-alien relations, whether serious or humorous, others take the metaphorical route, using the guise of alien sex to say something about human sex, relationships, or gender differences. Each story is preceded by a short introduction by Datlow, and followed by a few words from the author explaining their inspirations or intentions in writing it. That last is a plus for me, since I like getting into the heads of authors to see where they’re coming from.

Science fiction, obviously, has an interest in aliens. And let’s face it, everyone has an interest in sex. So it’s not surprising to occasionally find both interests coinciding in the same place. In this volume you’ll find nineteen tales of sex seen through the lens of science fiction (with a bit of fantasy and horror mixed in as well). These stories run the gamut, from thought-provoking to dull to incomprehensible; there is enough of substance here, however, to make this a worthy contender for the reader’s attention. The stories also vary in their approach to the anthology’s theme; while some are straightforward speculations on human-alien relations, whether serious or humorous, others take the metaphorical route, using the guise of alien sex to say something about human sex, relationships, or gender differences. Each story is preceded by a short introduction by Datlow, and followed by a few words from the author explaining their inspirations or intentions in writing it. That last is a plus for me, since I like getting into the heads of authors to see where they’re coming from.

On the lighter side of things we have Larry Niven’s “Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex,” a speculative look at Superman’s sex life. Also among the more humorous stories is Harlan Ellison’s “How’s the Night Life on Cissalda?”, about a trans-dimensional explorer who brings back an addicting orgasm-producing creature — “the most perfect fuck in the universe.” It’s typical Ellison irreverent weirdness, but fun. Also in this category is “The Jungle Rot Kid on the Nod” from Philip Jose Farmer, a self-proclaimed “parody-pastiche” that asks the question, “What if William Burroughs, instead of Edgar Rice Burroughs, had written the Tarzan stories?” Interesting concept, but since I can’t stand William Burroughs’ style I found this one unreadable.

On a more serious note there is “Her Furry Face” by Leigh Kennedy; it explores what happens when a primate researcher becomes attracted to an engineered super-inelligent orangatun. Lisa Tuttle uses “Husbands” to ask about the meaning of separate genders, and about what happens when one of them goes extinct. Bruce McAllister’s “When the Fathers Go” uses the alien sex idea to look at the lies people tell each other in order to keep relationships going. Michaela Roessner’s entry is “Picture Planes,” a poem portraying a destructive, imprisoning relationship between an alien and a human that mirrors too many real-life couples. “Roadside Rescue,” by Pat Cadigan, poses an intriguing problem: what if you engaged in sex with an alien and didn’t even know it — simply by performing some innocent everyday action?

Then we come to my two favorite stories of the lot. “War Bride,” by Rick Wilber, is a depressing picture of a man who, in order to escape impending destruction, becomes the sexual pet of brutal alien invaders. This one, too, is a reflection of a scenario surely played out many times in human history, and is a stark reminder of the conditions people will subject themselves to in the name of survival. “And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side,” by James Tiptree, Jr., is possibly the most thought-provoking piece of work in the book. It takes the position that our deep-seated biological imperative to spread our genes far and wide might become maladaptive when we encounter aliens, with whom mating is sure to be sterile. Tiptree deftly gets across the tragedy of this uncontrollable, misdirected drive, of eagerly striving toward a hopeless and unobtainable goal, to the diminishment of the species.

There are other stories — by Scott Baker, K. W. Jeter, Edward Bryant, Geoff Ryman, Connie Willis, Richard Christian Matheson, Lewis Shiner, Roberta Lannes, and Pat Murphy — that I didn’t mention for one of several reasons. Some are fantasy or horror and thus not really my cup-o-tea. Some were simply of no interest to me. And a few inspired me to ask that oh-so-frequent question, “what the hell was the editor thinking by including that?”

There are some winners and losers here, like most anthologies. But hey, how can you pass up a book about SEX? And ALIENS!? You know you cant!